For the four weeks leading up to and going beyond Easter, we’re looking at the life of Peter. Because he’s so often at the center of both the brightest and darkest moments in the Gospels, he has always been a source of hope and inspiration for those endeavoring to follow Jesus.

Theologian Walter Wink calls it the Myth of Redemptive Violence.

It is the belief “that violence saves, that war brings peace, that might makes right.” As he observes in his book The Powers That Be, “It is one of the oldest continually repeated stories in the world.”

Using force to make our enemies pay just seems so natural. Isn’t that what we have to do?

Scroll through your Netflix menu this Easter weekend and you’ll find thousands of films about cops, ninjas, secret agents, crime families, and comic book superheroes. What most of these movies have in common is a “necessary” violent confrontation to set things right. It seems that the only way to stand up for what is right is to start shooting, karate-kicking, or bombing.

Avengers: Endgame just surpassed Avatar as the highest-grossing film in Hollywood history. Both epics rely on the formula of the Big Fight at the End to destroy evil, as do 19 of the other 25 most lucrative movies of all time.

In the real world, people of faith sometimes come to the same conclusion. If our call is to fight God’s enemies, we may have to resort to violence, right?

In her 2020 book Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, Kristin Kobes du Mez notes that a national emphasis on “militant masculinity” swept conservative churches in the wake of 9-11. At Christian conferences, men were called to thank God for the gift of testosterone, “pick up their swords” to defend their families against atheists and political correctness, and to eradicate the “wussification of America.” Speakers urged men to “forget the Jesus who turns the other cheek.” Christian mixed martial arts academies emerged as a new way to do ministry – “where feet, fists, and faith collide.”

The irony, of course, is that all four Gospel accounts end with the ultimate showdown between Good and Evil. Jesus entered Jerusalem for the final time. His enemies were arrayed against him. This wasn’t a movie. This really happened in space and time.

And Jesus lost. On purpose.

To the surprise of everyone – perhaps especially Peter and his fellow disciples – Jesus wasn’t following the ancient script of the Myth of Redemptive Violence. He was living out a deeper story – that redemption would come not from a God-anointed warrior, but from a suffering Messiah. The only way to experience the victory of Easter was to lose – or appear to lose – the climactic “final battle” on Good Friday.

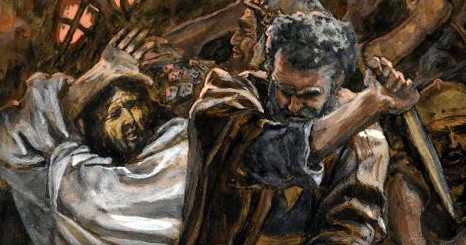

Peter couldn’t see it. Always eager to do something for God, he was prepared to fight for his Master. According to John 18:10, he pulled out a sword and sliced off the right ear of a man named Malchus, a servant of the high priest.

When the disciples asked Jesus if he wanted them to fight for his freedom, his response, as reported in the Gospel of Luke, was unambiguous: “Enough. No more of this! Those who live by the sword shall perish by the sword.” Whereupon he reached out and healed the man’s ear.

Bible scholar Dale Bruner points out that whenever followers of Jesus resort to physical force, all they end up doing is cutting off the ears of other people, making it harder than ever for them to hear the Good News.

Here we should pause to marvel at the fact that even though so many characters in the Bible are unnamed, we actually know the identity of the man who lost his ear. It must have been interesting when Malchus went home later that night. We can imagine the moment when his master, the high priest – one of those committed to killing Jesus – asked, “So, did everything go smoothly during the arrest?” How would Malchus have reported the events of the evening?

We also need to acknowledge a sobering reality of Christian history: Followers of Jesus have sometimes gone to war with crosses on their shields. It’s tragic that Jesus’ cross – the very place where God made peace with the world – has occasionally been distorted into a military banner. We can say with certainty that Jesus himself never gave an order to do such a thing.

He did, however, speak plainly about battling evil. We must always resist. But we must never, at a personal level, resort to physical violence.

The opening line of St. Francis’ famous prayer is always a safe place for us to land: “Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.”

Does God want us to bet our lives that violence will somehow make our families, our communities, our nation, and our world a better place?

Enough. No more of this.

As Peter ultimately learned – the hard way – there are so many better ways to conquer the world.