To listen to today’s reflection as a podcast, click here

“Let me play devil’s advocate for a few minutes.”

Most of us have heard that before. Someone makes a point or proposes a plan. It definitely has merit, and listeners nod their heads in agreement.

Then one person decides to push back – not necessarily because they disagree with what they’ve heard, or can think of anything better, but because testing the strength of a proposal is always a healthy thing to do. “You say we should do thus and so, but what if we can’t make that deadline? Or the weather turns ugly? Or the bank turns us down?” Or any number of other possibilities that might doom an otherwise brilliant plan.

The devil’s advocate is someone who intentionally looks on the dark side. Whether they end up validating the original idea or blowing it to smithereens, they’ve played an important role in a group’s process of discernment.

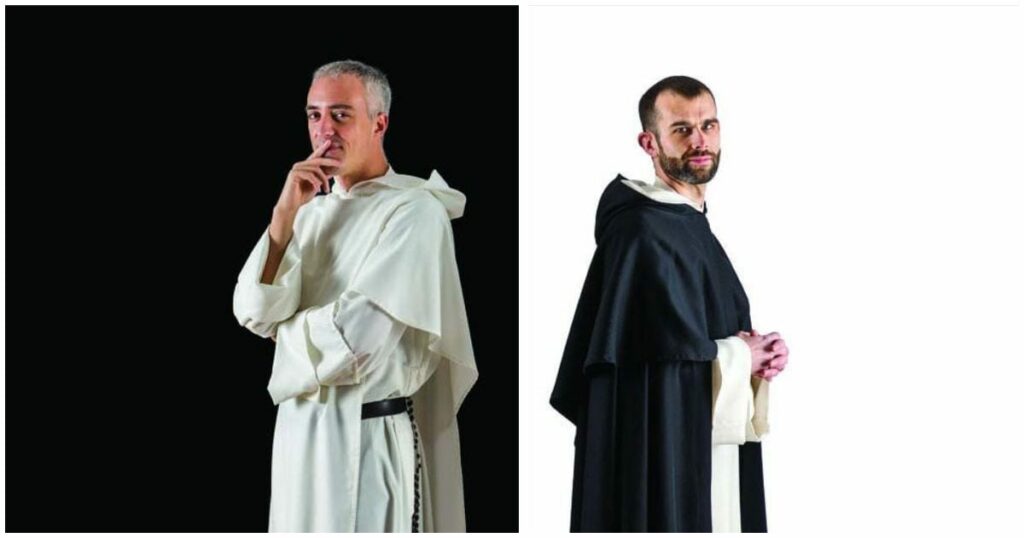

Interestingly, the Catholic Church used to employ such an individual. Beginning in 1587, a lawyer was given the official title promotor fidei, or Promoter of the Faith. Unofficially he became known as advocatus diaboli – the Devil’s Advocate, or the one who tries to put into words Satan’s strongest case against a candidate for sainthood.

After all, if a man or woman was being promoted for canonization, someone had to do some serious background checks.

Had significant character flaws been overlooked? Would the “miracles” attributed to this candidate turn out to be nothing more than hearsay? Had this individual’s ministry been misrepresented?

It was the Devil’s Advocate’s job to play the skeptic, to sniff out fraud, and to make, if possible, a watertight case that this person was unqualified for sainthood.

It was up to the Church not to ignore such negative feedback, but to take it into account. That’s never an easy thing to do.

Pope John Paul II reduced the role of the Devil’s Advocate in 1983. But the Vatican still has the freedom to do spiritual background checks on candidates for canonization. In 2003, for instance, when the Church was considering the late Mother Teresa’s case for sainthood, officials chose to interview one of her most outspoken critics – Christopher Hitchens, one of the so-called New Atheists. Did he have specific information or perspectives that would doom her candidacy?

It’s unlikely that any of us will ever have to play devil’s advocate with regard to the spiritual standing of another human being.

But that doesn’t get us off the hook.

All of us, in one fashion or another, have to decide if the case againstGod is so strong that we simply cannot entrust ourselves to him as Ruler of the cosmos.

For many people, the Holocaust is a dealbreaker.

Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel recalled seeing a wagonload of dead children being thrown into a flaming ditch during his first night as a prisoner at Auschwitz. He writes, “Never shall I forget…the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed… Never shall I forget those moments that murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never.”

How can we affirm that “God is great and God is good” in the face of God’s inexplicable silence at Auschwitz?

Then there’s Agnes.

Even as a young girl, her only desire was to please God – “to love Jesus as he has never been loved before.” She welcomed the call to become a missionary. She journeyed far from home. “My soul at present is in perfect peace and joy,” she wrote in her journal. She felt overwhelmed by the nearness of God’s presence.

Then, seemingly out of the blue, that nearness vanished.

For no reason she could ever discern, Agnes lost her sense of God’s proximity, God’s love, even God’s existence. She didn’t quit serving and didn’t stop praying. But the sense that she had somehow “lost” God haunted her thoughts. “My God,” she wrote, “how painful is this unknown pain… I have no faith.”

Except for one brief intermission, her inward experience of dryness and doubt lingered for the better part of 50 years.

As a Catholic nun and founder of the Missionaries of Charity, a religious community dedicated to serving “the poorest of the poor,” she reckoned it would be better if the world never found out about the struggles that filled the pages of her journals. She insisted they be destroyed upon her death.

But wise people chose not to do so. That’s how the world became acquainted with the inner life of Agnes, better known as Mother Teresa of Calcutta.

When word of her decades-long spiritual struggles became known, atheists like Hitchens pounced. “She was no more exempt from the realization that religion is a human fabrication than any other person, and that her attempted cure was more and more professions of faith could only have deepened the pit that she had dug for herself.”

It seemed as if the Devil’s Advocate had been handed a slam-dunk case.

But the strangest thing has happened since Mother Teresa left us almost 30 years ago. She has become not just one of the world’s great examples of compassionate service. She’s also revered today as a “missionary” to those who doubt.

That’s because she never stopped believing, in her heart of hearts, that God is really God. She did not give her feelings, in other words, permission to cast the deciding vote on the nature of Reality.

Nor should our own feelings during these last few days of spring be granted the power to cast a spiritual veto – to determine, above every other line of evidence, whether there is in fact an infinite-personal Creator who is closer to us than our next breath.

A faithful devil’s advocate would no doubt insist on revisiting that important question: Are there good reasons for believing that God cannot be trusted in a world torn by suffering?

Why does God so often seem so far away? How can we reconcile divine love with the Air India jet crash, senseless gun violence in Minnesota, deadly flash floods in Texas and West Virginia, and yet another war gearing up in the Middle East? And that’s just the past week.

We must be honest. We rarely receive final answers to such questions in this world.

But there are a few things that we can know.

We can know that just because we ourselves cannot see any good emerging from a particular situation doesn’t mean an infinite God is limited by our imagination. If God is God, he is free to have reasons to permit tragedies, even though we cannot fathom, for now, what those reasons might be.

We also know that most people would acknowledge that the most important lessons they have ever learned – the very things that have most shaped their character – have come through disappointment, struggle, and loss. Sometimes it is God’s mercy not to rescue us from trouble.

Followers of Jesus know that they live in the hope that their suffering means something. “Suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope. And hope doesn’t disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts” (Romans 5:3-5).

So where is God when it hurts?

According to everything we know from Scripture, God never leaves the side of the one who is hurting. He weeps with those who weep.

And God never stops rallying us to be his hands and feet in a world that is more desperate than ever to experience his justice, mercy, and love.

The devil’s advocate may think he has a ripping good case.

But “we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the Righteous One” (I John 2:1).

And he’s got a better record in God’s court than Perry Mason.